NOTE: as the kids say, SPOILER ALERT!!!

The Bad Sleep Well departs from Kurosawa’s previous adaptations in several distinct ways. Firstly, this is a free adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. That is to say that, unlike Throne of Blood, The Bad Sleep Well takes elements—key themes, plot devices, and characters—from Hamlet and throws them into a completely new and unique narrative. This is the first of Kurosawa’s adaptations that is truly Shakespearian in its creation. Certainly Throne of Blood is Shakespearian in nature, but its creation (even though it departs from the original in significant ways) is essentially based on the framework of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Although it takes place in 16th century Japan it retains narrative qualities directly from the original play. The Bad Sleep Well on the other hand is a based on the source material, but is a completely new narrative, with many differing elements. With the exception of The Tempest, all of Shakespeare’s plays were based on pre-existing material (be it legends, plays, historical documents) that he altered dramatically to create an artistic vision that is often times unrecognizable from the original. With the creation of The Bad Sleep Well Kurosawa takes Hamlet and uses it in the very same manner. Nishi is certainly “Hamlet-like,” but he is not Hamlet, and the same can certainly be said of all the other characters that populate the world of the film. Every film that has been examined thus far (and will be examined) was written by Kurosawa, it is his vision that ends up being turned into the final product—he is directing his own work. Every adaptation is his own creation, and The Bad Sleep Well is a creation that stands alongside Shakespeare. It is almost unnecessary to even mention that the film is based on Hamlet, as it creates such a different atmosphere. This is, from a literary perspective, the most impressive film that this study has uncovered thus far. The Bad Sleep Well is not an adaptation—free or otherwise—but instead an original creation of the highest order.

The opening shot of the film sets the rigid tone of the world that will begin to be unveiled. Servants stand milling about, until from off screen, from the direction of the camera, a bell rings and the relaxed servants spring into tense action. The shot shifts to show these servants now lined up on either side of the source of the bell, an elevator. They await the arrival of their betters. In the very first moments of a film, which is quickly becoming a strong theme in all of the examined work, Kurosawa artfully displays the main theme of the entire film, firmly establishing the proceedings. Loyalty and hierarchy (and betrayal of this order) will be the main themes of the film, orbiting constantly against the overwhelming gravity of revenge.

Nishi, unlike Hamlet, is not an ineffectual spirit of vengeance. The story begins with perhaps Nishi’s first machination of revenge—the suicide-referencing wedding cake. This is certainly not the first action that has been taken by Nishi in his quest to topple—rather completely destroy—the men who brought his father (and numerous others) to the final breaking point. It is his wedding that is taking place, and he is marrying the grand villain (in essence). This event itself is in medias res, there have certainly been many steps in Nishi’s plan to reach this place where truly hands-on revenge can begin (which we will learn more of as the story progresses), but the wedding cake is the first event shown in the film. The wedding also poses some tricky questions for Nishi, and his abhorrence of the kill or be killed corporate world.

In order to set himself up in a position to truly exact revenge on the men he hates so fully, Nishi must in some ways become one of them. He must also become well studied in the arts of deception and violence. Much in the same way that Hamlet struggles with the similarities between himself and Polonius, Nishi struggles to remember his purpose and to focus his energies in the direction of the men that he now—albeit superficially—owes his allegiance (and fortune) to. The complexity of this situation creates an interesting question: have hate and vengeance driven Nishi into his somewhat desirable position amongst the corporate elite, or has an unknown desire for power and fortune lead him to this point? There are no definitive answers to these questions given within the film itself. Certainly Nishi and his co-conspirator hate the men at the top, giving testimony as to how their fate was intertwined even from their jobs at the old factory (which is where they tell the story, and the setting of the penultimate moments of the film), but does Nishi begin to doubt whether he need truly destroy these men? Is his hatred dulled by the love of Yoshiko? This latter question seems rather likely.

Nishi’s partner, Itakura, warns him against falling in love because it will derail the purpose of their mission. Wada, although understanding the evil nature of Iwabuchi and his lackeys, is shocked by the visceral means (and the over-riding hatred) that Nishi employs to gain his revenge. Wada attempts to intervene by placing Yoshiko in Nishi’s path to her father. This plan is only half successful. Nishi does feel genuine love for Yoshiko and is hesitant to hurt her, but his hatred wins the day and he proceeds with his plan of destruction. Even so, her inclusion in the scheme starts the cogs of destiny and Nishi’s fate is sealed. Iwabuchi uses his daughter to discover the hideout and has Nishi killed, effectively ending the threat. But has Nishi’s plan truly failed? Iwabuchi will not face official punishment and disgrace, but his punishment will be something far more damning. In the final scene of the film he sees that his daughter has become mad with grief, and his son wants nothing to do with him. He has saved his corporate soul while sacrificing his human soul. There will be no sleep for Iwabuchi in the future.

Kurosawa deftly shifts from this family shattering event to Iwabuchi fawning and scrapping before his superiors in the last action of the film. Although he has damned himself, created a rift with his children, and destroyed countless lives, he continues to adhere to the strictures of corporate existence. His lust for power and position is absolute. It is unclear what his final fate shall be, but, whatever happens, this is an intense indictment of both the Japanese corporate world and the fickle heart of humankind in general. There are no ties that bind completely. The film begins with a wedding, a social show of union—that is nothing more than a revenge motivated farce—and ends with the dissolving of a seemingly close-knit family. Blood, bonds, and oath are no match for greed and revenge. Iwabuchi grovels in front of his superiors, keeping his oaths to them, but only in a desire for power. If the pragmatism of this desire dictated that he betrayed his superiors he would not hesitate to do so. Man is in his finest state subject to the impulses of his nature.

Outside of Yoshiko there is no character in this film that does not function—feed—off the most base of emotions. Her purity and altruism is perhaps the final piece that shoves her into irreconcilable madness. While the other characters of the film see the evil of others within themselves, she has worn her defect as a physical illness from an early age—her soul is pure. Crushed as her brother and Itakura may be, they see that this is the way of the world. Evil things will always exist and sometimes (perhaps most times) win the day. The fate of Nishi, a man who truly loved all of her, is unfathomable. She shrinks inside herself and her dulled visage is the final piece of Nishi’s posthumous revenge. It is the sight of his daughter’s suffering, and the knowledge that he inflicted it upon her, that puts Iwabuchi in a mental prison for all time.

The Bad Sleep Well stands as a sort of turning point in Kurosawa’s career. His first great upward rise is beginning to decline and there will be bleak years in the not so distant future. Never the less, the film stands as a testament to the growth of his adaptive abilities, his skill as a writer and an artist. What would happen if Hamlet possessed a steel will and tremendous spiritual vitality? The Bad Sleep Well answers that question quite beautifully, while standing apart from Shakespeare’s play as a unique criticism of modern capitalism and the dangers of greed.

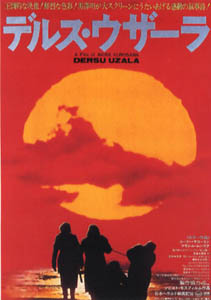

Dersu Uzala is a very unique film within Kurosawa’s body of work. Unlike previous ventures such as Throne of Blood or The Bad Sleep Well, Dersu Uzala is haunting not in a foggy and obscured manner, but in its gutturally bright brilliance. Nature, when seen through Kurosawa’s lens, and captured on 70mm film takes on an almost ethereal beauty and transcendence that has the same evocative presence that scenes in Spider’s Web Forest or the dirt pit have in the previously mentioned films. Kurosawa has always been adept at capturing the strength of nature in his work and exploring humankind’s relationship, be it directly or indirectly, with the wilder elements of the world. With Dersu Uzala he takes this process one step further, placing humanity beneath nature, this is not a relationship of equality—humankind must bow to nature at every turn or be buffeted from the land of the living. There is a brooding quality to the presence of nature that only truly appears perhaps (and only to a much smaller degree) in Throne of Blood’s forest scenes. From the initial scenes with Arseniev looking for Dersu’s grave, to the final scenes with the same connection, the body of the film is fraught with peril and tension. The wilds of Siberia are unforgiving.

Dersu Uzala is a very unique film within Kurosawa’s body of work. Unlike previous ventures such as Throne of Blood or The Bad Sleep Well, Dersu Uzala is haunting not in a foggy and obscured manner, but in its gutturally bright brilliance. Nature, when seen through Kurosawa’s lens, and captured on 70mm film takes on an almost ethereal beauty and transcendence that has the same evocative presence that scenes in Spider’s Web Forest or the dirt pit have in the previously mentioned films. Kurosawa has always been adept at capturing the strength of nature in his work and exploring humankind’s relationship, be it directly or indirectly, with the wilder elements of the world. With Dersu Uzala he takes this process one step further, placing humanity beneath nature, this is not a relationship of equality—humankind must bow to nature at every turn or be buffeted from the land of the living. There is a brooding quality to the presence of nature that only truly appears perhaps (and only to a much smaller degree) in Throne of Blood’s forest scenes. From the initial scenes with Arseniev looking for Dersu’s grave, to the final scenes with the same connection, the body of the film is fraught with peril and tension. The wilds of Siberia are unforgiving.