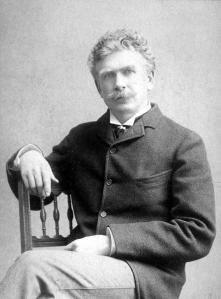

Bill Sienkiewicz and “The Whale.”

by Ezekiel Fry

Several years ago I stumbled across a Barnes and Noble edition (I know, not exactly the sexiest publisher) of Moby-Dick with perhaps the best cover art I had yet encountered in relationship to Melville’s monstrous book. I was fascinated by the haunting qualities of the piece, the murkiness of its form. The whale is barely visible, and what is seen is viewed through the darkness of the ocean, or some other subterranean pit. There is little to no definition where the tail ends and the depths begin. The two entities, the whale and the sea, are merged into one. Add to this the clear signs of a hasty descent and it almost appears that this tail, caught in vigorous motion, might well be diving down to the foundations of the earth with Ahab and Fedallah in tow. This could very well be the final, unseen image of Melville’s book. I was, and continue to be, astonished by this dynamic piece of art. As I held the book (which I subsequently purchased and filled with asterisks and marginal notes, and finally, in a drunken outburst, bequeathed the whole damn thing to a wandering sage on the streets of Olympia) in my hands I wondered what type of artist could create such an evocative image, touched so thoroughly with what I believed to be the central mystery of Moby-Dick? I flipped the book over and, sure enough, there was a name I readily recognized: Bill Sienkiewicz. I was both shocked and not surprised. Sienkiwiecz! Of course. How could it be anyone else?

Bill Sienkiewicz, for any of you comic book heroes out there, is a household name. For the rest of the world go read this and then return to this entry: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Sienkiewicz

Back? Okay. So there you have it. An artist about as cutting edge as you can get in the mainstream of comics. And with a handle on the Whale. Something that I do not believe appears in the above-linked wiki profile (although I am sure it has been meticulously documented in the bibliography, if you made it that far) is his work on the “Classics Illustrated” adaptation of Moby-Dick and here is a link to Sienkiewicz’s own website, and a gallery of his work on the Whale: http://www.billsienkiewiczart.com/gallery.asp?sc=BSMOB. For this reason I was not surprised when I discovered that it was indeed Bill Sienkiewicz who had painted the cover to the book I was holding. He, like Jonah before him, and so many of us wild-eyed pilgrims down through the years, has spent an immense amount of time within the belly of the Whale. There is no other contemporary artist (in fact no artist period that I have ever encountered) with a better grasp of this subject. His work approaches the sublime, in a truly Kantian sense. Sienkiewicz knows the Whale, but that is just one man’s opinion. In preparing this entry I discovered a wonderful piece in Laura@popdesign’s blog “Animalarium” which presents many varied artistic interpretations of Moby Dick in succession (including the Sienkiewicz painting that I have included here). Check it out and decide for yourself what image of the Whale feels best. The presentation, which includes excerpts from the book, is just fantastic. I really enjoyed the whole experience and there are certainly some absolutely mind-blowing representations of the whiteness. Happy hunting!

http://theanimalarium.blogspot.com/2012/01/white-whale.html